Numbers don’t lie: Women’s wages not what they seem

Prioritizing athletics over academics

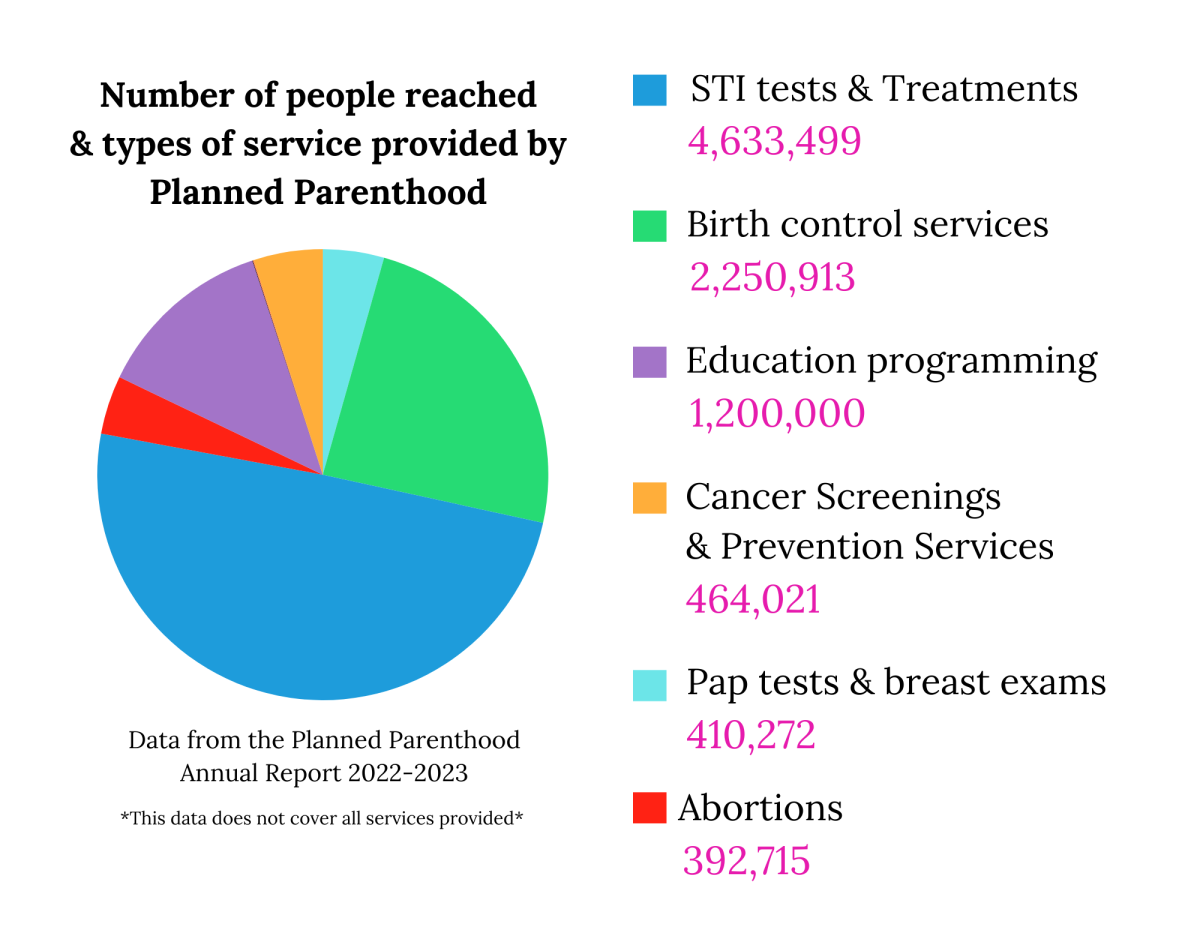

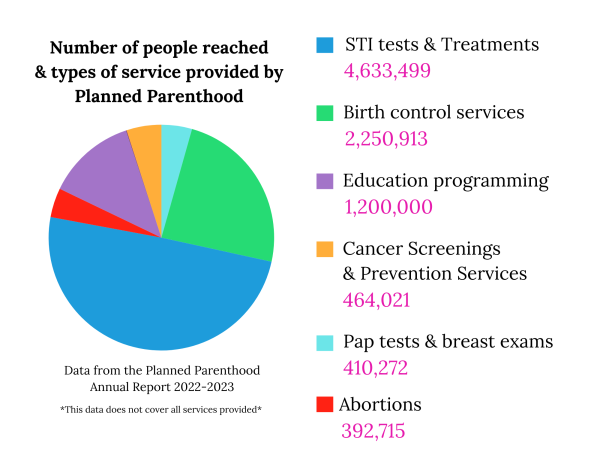

There are 32 women in the top 100 highest-paid employees at Coastal Carolina University, but they only make 26% of the highest wages.

The South Carolina Freedom of Information Act requires the public institutions to report the salaries of all employees who earn more than $50,000 annually. According to the state’s Department of Administration state salaries query, out of the $17 million earned by the top 100 highest-paid faculty and staff members, only $4 million goes to women on the list

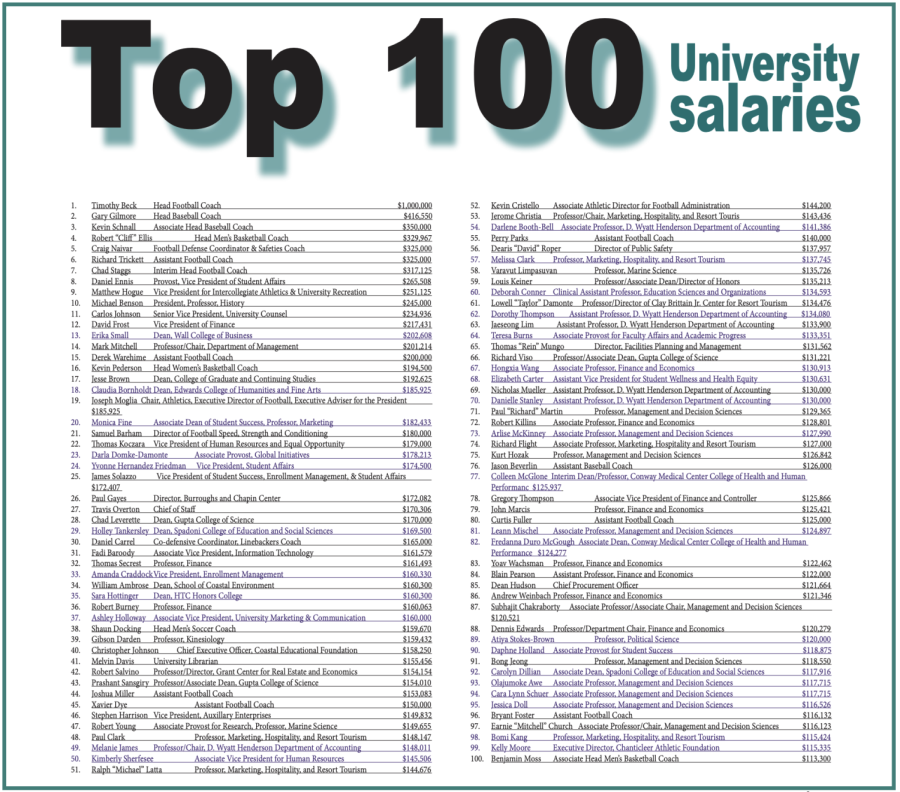

Dean of the Wall College of Business Erika Small, who makes $202,608, moved up two spots at the University from last year and is now ranked 13th. She is the highest-paid woman working at the university.

Men hold all the top 10 spots, earning a total of $3.8 million, which makes up 22% of the entire top 100 salaries. Eight of those men are athletic staff, and Provost Daniel Ennis and President Michael Benson are the other two. Ennis, who ranks 8th, makes $265,508.

Head Football Coach Tim Beck earns the most money at CCU with a salary of $1 million, not including bonuses. To put this in perspective, 10th ranked President Benson makes $245,000, less than a quarter of Beck’s salary.

The salaries of all 68 men on the list equal $12.6 million, or 74% of the top 100.

Executive Director of the Chanticleer Athletic Foundation Kelly Moore just barely makes the list at No. 99 as the highest paid woman in the athletic department.

Last year, Head Women’s Basketball Coach Jaida Williams was the highest paid Black woman in the top 15 highest paid employees. Today, the highest paid Black woman is Associate Vice President of University Marketing and Communication Ashley Holloway at No. 37. Vice President of Student Affairs Yvonne Hernandez Friedman ranks at No. 24 for the top 100 as the highest paid non-white woman at CCU.

Pamela Martin, a member of the President’s Council and professor of political science, served as the chair of faculty welfare committee for the Faculty Senate. In Martin’s previous role, she handled topics regarding faculty compensation and conduct.

“If you look across the country at academic institutions, you’re going to find that it’s traditionally males that are in the top paying spots,” Martin said.

Martin said faculty salaries are completely separate from athletic salaries because coaches do not go through the academic peer review process. However, she said it is valid for the football coach to make as much as he does.

“I mean, is it demoralizing that, you know, academics spend a lot of time with students, and we care about students, and we’re teaching them, etc.? Sure, sometimes,” she said. “On the other hand, you can’t be blind. We function within a market system for pay and that’s what Coach Beck can demand. I applaud him for negotiating.”

Martin emphasized the market system sets up pay for coaches, so the market itself is unfair rather than putting blame on Coastal. Associate Professor of political science Kaitlin Sidorsky said she is not surprised athletics draws in a large amount of money, specifically men.

“We should consider who’s in those jobs, how to be compensated for them, and why they’re not towards the top of the list,” Sidorsky said.

David Frost, Coastal’s senior vice president for finance and chief financial officer, said funding for faculty salaries comes from two primary sources. One source, he said, is from appropriations from the state of South Carolina. The other source is from tuition and student fees.

For athletics staff salaries, Frost said there are different funding sources. In addition to athletic revenues, student athletic fees also contribute to their salaries. He said the current athletic fee for students, which is included in tuition, is $370. For part-time students, he said the fee is $25 for every credit hour they take.

“In return, students get admission to games,” Frost said.

Martin was part of Faculty Senate when the newest compensation model was developed in 2015 to lay out rankings for tenure and non-tenure track promotions for faculty. At most universities, the starting tenure track rank starts with assistant professor then associate professor to professor.

Essentially, Martin said tenure is what protects a faculty member from being fired and helps them practice academic freedom in their research. The tenure track process is determined through a peer-review process from the department, college, dean, then provost.

Within the compensation model, she said the highest pay raise only occurs every six years. Another component to faculty salaries is compression to match the salaries of those who were hired during these six years.

“Faculty salaries get compressed when you’re sitting there for six years without a pay raise and a new person gets hired at market rates,” Martin said. “That happens all the time because the market forces change.”

According to Martin, faculty salaries have not been decompressed at 100% since 2015. Faculty salaries are also determined by the cost of living where the state legislature mandates the University to give pay raises.

Frost said South Carolina will do cost of living adjustments for all state employees every year. He said that some years will receive no changes, but that recent inflation costs will likely lead to a 3% increase in pay adjustments this year compared to last year’s 2.5% increase.

To include and promote more women on the top 100 list, Sidorsky said it is important to hire managers who understand how much the University offers to men versus women, and white women compared to women of color.

“I’m not even saying that [CCU is] trying to be discriminatory or offer women less on purpose,” she said. “It just might be subconscious.”

She said she has hope qualified women will come to the top and be treated as such in their positions.

Professor Emerita Sally Hare said she remembered her experience of going to her bosses and asking for pay equal to her coworkers ever since she started working as a professor at the university in the ‘80s. While she said attitudes in current generations have changed, she said there’s still room for improvement.

“It certainly takes a long time to make change,” she said.

Hare said professions that grow to become woman-dominated like teaching have historically seen decreases in overall salaries for both men and women.

According to a report from Sylvia Allegretto and Lawrence Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute, even men who worked in teaching in 2015 earned 24.5% less than those who worked in comparable profession dominated by men. In 1979, men in teaching earned 22.1% less.

“The large wage penalty that male teachers face goes a long way toward explaining why the gender makeup of the teaching professions has not changed much over the past few decades,” the report said.

Hare said while money can be a taboo topic to discuss, it’s important for both women and men to speak out on salary issues for there to be change.

“It’s becoming more public than it ever has, and I think that’s a good thing. I don’t like secrets. I don’t think they’re useful,” she said.

Kadence • Mar 18, 2023 at 6:24 pm

Wonderful piece

Kadence • Mar 18, 2023 at 6:23 pm

Wonder piece