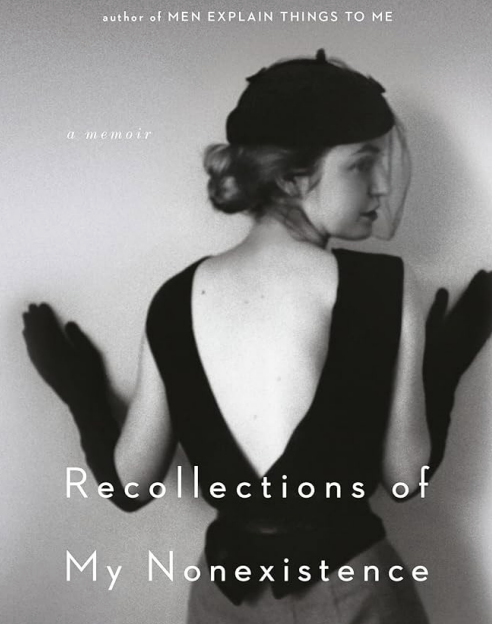

Rebecca Solnit’s memoir, “Recollections of My Nonexistence,” spoon fed my soul in ways I hadn’t imagined possible. As a woman, reading it made me feel as if I were living and not just surviving.

This memoir reminded me once again why I fell in love with literature in the first place. But more importantly, that I am not alone in my frustrations of being a woman.

Solnit shares her story “not because it is exceptional, but because it is ordinary.” She explains that this violent reality we are accustomed to “is paved over with women’s fear and pain, or rather with the denial of them,” but it can’t change “until the stories that lie underneath see sunlight.”

Women, are you aware of the undeclared war you’ve been fighting all your life?

I thought I was, but Solnit’s memoir sat me down and force fed this often-ignored reality down my throat. Her words devoured me with their raw honesty and depiction of this battle, we as woman, have always fought.

As women, we are constantly being told what not to do, what to do, what to avoid, etc., and this has caused us to never stop imagining our own murders in grave detail. Solnit exposes the cruel reality where we are repeatedly reminded that “the worst things that happened to other women because they were women could happen to you because you were a woman.”

She references many pieces of ancient and current literature that feature women only in violent ways. Whether they’re raped, murdered or tortured, they often resemble a corpse. What else could a young girl subconsciously imagine herself as when she grows up, other than dead?

Fear is instilled in us every second of our lives, and I’d argue that living isn’t the most suitable term for constantly trying not to be raped, assaulted, killed or tortured.

We feel the pain of our sisters, knowing it could have been us. Solnit’s words sting with truth, that even if you weren’t the one killed, “something in you was, your sense of freedom, equality confidence.”

While you’re avoiding death, you’re imagining your own, even if you don’t consciously realize it.

For years I’ve found a strange comfort in true crime, and most nights a documentary about a serial killer brutally raping and murdering women has put me right to sleep. Recently I’ve found myself wondering why something so horrific could bring me such relaxation.

Maybe I’m a psychopath. Or maybe, as Solnit explained, violence has intergraded itself into every aspect of my life and those of my gender, that its normalcy brings me comfort. Not to mention there’s always a pretty good chance the main character is going to be a woman for once.

A couple weeks ago I overheard a heated conversation about rape occurring between two men. One claimed he’d kill the entire bloodline of a man who put his hands on his daughter. The other, feeling less strongly, said he’d do some serious damage if someone touched his sister.

I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but this bothered me for weeks until I came across this excerpt from Solnit’s memoir that opened my eyes to why.

It was never about the woman; it was about his ownership and guilt. It was the idea of men wanting to protect “what was theirs to protect or destroy…” Despite the horrific trauma the woman endured, “the plot was about his grief that he’d failed to protect, or his revenge against other men, and sometimes he destroyed her himself, and the story was still about him.”

“The story was still about him,” sits underlined in thick ink.

I read most of this book sitting by the pool with my friend. I read excerpts aloud, while she sat and listened in awe at the truth of Solnit’s words. It was then I realized that all genders should read this book at one point in their life.

I’d like to imagine a man could read this memoir and not feel as though it is his responsibility to protect women, but to simply acknowledge this war that has been declared on us. Maybe he’d want it to change.

Solnit gave me the answer I had been longing for, the reason why I had been so upset at something I thought should’ve made me feel better.

Can’t I be in my own hands rather than someone else’s? Is it so absurd to want to own the right to my own body?

The last lines in the acknowledgements section read, “Thank you feminism. Thank you, intersections. Here’s to the liberation of all beings.”

Truly, thank you Rebecca Solnit.